Tse' Bit'ai via the Original Route (5.9 A0)

October 29, 2010

As the Navajo Ancestors fled an attacking tribe, they prayed to the Great Spirit for their salvation. Suddenly, the ground lurched beneath their feet and began to rise. As the People saw the enemy tribe recede, they looked down to see that a giant bird bore them on its back. The Bird gracefully soared upward and began to fly toward safer lands. Days passed, and the Bird began to scout the land for a better place for its People to live. Spotting a suitable location in the desert near a river with distant mountains, the great Bird circled thrice and landed. As the People moved out onto the land, the now exhausted Bird folded up its wings to rest. Unfortunately, all was not well. A giant man-eating dragon named Cliff Monster climbed up onto the weakened Bird's back, built a nest and trapped the Bird. The People were furious and immediatley sent their Monster Slayer up to grapple with the beast. A tremendous battle ensued, and in the chaos, the Bird became gravely wounded. In a fury, Monster Slayer cut off Cliff Monster's head and cast it off into the distance. As Cliff Monster's remains were cast out, they turned to stone as they touched Earth. Its head formed Cabezon Peak to the east, and its coagulated blood formed the Great Dike immediately south of Tse' Bit'ai. Deep scratches and grooves were carved down the sides of the Bird as Cliff Monster's blood ran freely during the battle. Sadly, the victory was bittersweet, and a great tragedy soon came upon the People. The Bird had become fatally wounded during the struggle. Rather than let the Bird perish, Monster Slayer used his power to turn the Bird to stone so as to preserve and honor its gift to the People. Now a great rock stands just as Tse' Bit'ai rested: with its wings stretched up toward the heavens.

Legend says that young Navajo would scale the sheer walls of Tse' Bit'ai to gain visions. They eerily described the lofty summit perch where they would survey the People's land.

Legend says that young Navajo would scale the sheer walls of Tse' Bit'ai to gain visions. They eerily described the lofty summit perch where they would survey the People's land.

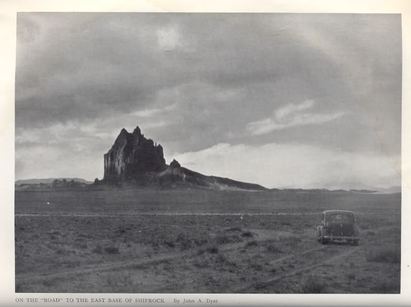

Tse' Bit'ai first gained attention from the European settlers as they traveled across the plains and spied a great rock looming above the desert floor from many miles away. As they grew closer, they imagined a large ship sailing gracefully with masts made of stone. They aptly named it Ship Rock, knowing nothing of the Peoples' history. Craning their necks up, the settlers were amazed at the rock's size. Ship Rock is indeed immense and rises a sheer 1,900 feet in a third of a mile. At dawn, its shadow can stretch for miles across the flats. The geology is striking and varies dramatically, giving it a patchwork appearance. The lower walls are often formed by crumbling basalt while the upper ramparts are breccia tuff. The remoteness of Ship Rock also creates a puzzle of perspective. Lines that appear as hand cracks from a distance prove to be 20 foot wide chimneys up close, while towers that appear small are in fact hundreds of feet tall.

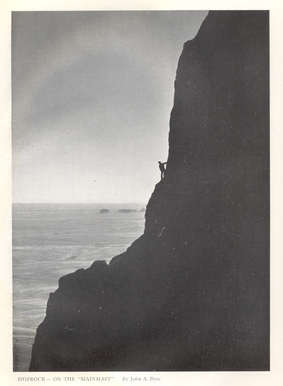

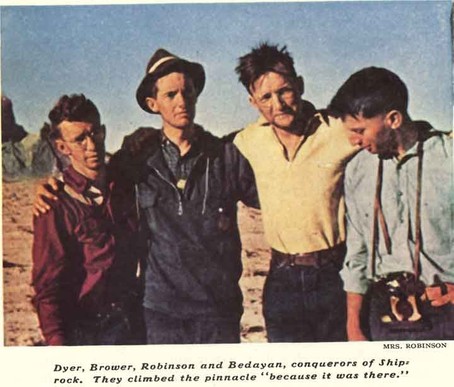

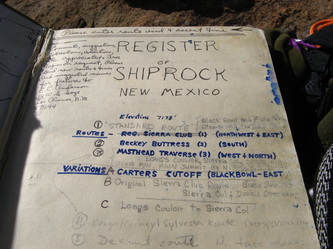

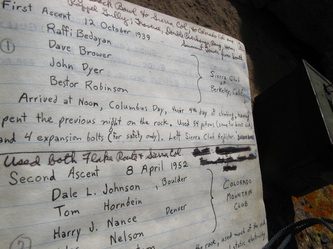

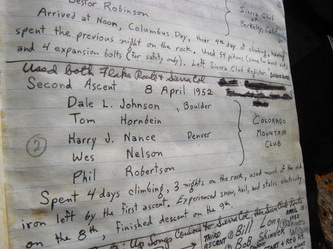

It was many years later before Ship Rock began to attract climbers. By the 1930's, numerous North American ascents had been made, and the list of challenging, unclimbed peaks was growing shorter. After stunning ascents of Canada's Mount Waddington and Wyoming's Devil's Tower in the early 30's, the climbing world turned its attention to Ship Rock. It had been attempted a few times but promptly rejected all parties with little to zero progress gained. Ship Rock gained the notoriety of being the last great challenge in North America, and there was even a rumored reward of $1000. The early pioneers were determined and brave. Robert Ormes and other members of the Colorado Mountain Club made several attempts, and although they pushed higher than anyone else had previously climbed, they could not make a route work. The most memorable of Ormes attempts took place in 1937 and ended above the Black Bowl in the Colorado Col. Faced with a steep basalt rib, he attempted to lead a difficult pitch straight upward toward the summit. Far above his last piece, a foothold broke sending Ormes plummeting toward a single shabby piton placed only two inches into the rock. The force of the 30-foot fall slammed his belayer into the wall and miraculously the piton held (after bending 90 degrees). Shaken, the two retreated and Ormes soon wrote an article entitled, "A Bent Piece of Iron" chronicling the incident. It was published in the Saturday Evening Post and only served to fuel many's desire to summit Ship Rock. The CMC's efforts were taken over by the Sierra Club, and in October 1939, a party of their members assembled at the base. David Brower, John Dryer, Raffi Bedayan and Bestor Robinson all traveled from California for their attempt and proved well resourced with every ounce of beta available on the route. Their gear consisted of many things, but most notably they carried 1,400 feet of rope, 70 pitons, expansion bolts, and drilling equipment.

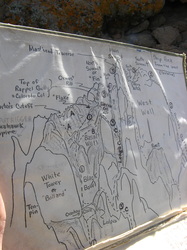

Working their way up the Black Bowl, the Sierra Club reached the basalt rib where Ormes fell in the Colorado Col. Deciding that the climbing above was too difficult, they instead climbed over the Colorado Col and made a series of rappels down the Rappel Gully to the other side of Ship Rock. Here they found themselves faced with a difficult traverse across a seemingly blank face to reach the easier upper slopes of the Honeycomb Gully. As they carefully traversed the face, they placed two expansion bolts to compensate for the total lack of standard protection opportunities. On the other side, they found themselves in a small cave above the immense walls of the lower Honeycomb Gully. With the cave's overhanging roof blocking upward progress, it took an entire days work to pass the Double Overhang via a short aid pitch. Finally on easier ground, the Sierra Club quickly found themselves at the now famous Horn. After throwing a rope over the feature, they stepped out over the immense west wall (and 1,800 feet of exposure) to climbed directly to the ledge above. One last pitch and some exposed scrambling later they stepped triumphantly onto the summit block. The first party retraced the route back down and celebrated their success. It took a decade before another party reached the summit again.

It was many years later before Ship Rock began to attract climbers. By the 1930's, numerous North American ascents had been made, and the list of challenging, unclimbed peaks was growing shorter. After stunning ascents of Canada's Mount Waddington and Wyoming's Devil's Tower in the early 30's, the climbing world turned its attention to Ship Rock. It had been attempted a few times but promptly rejected all parties with little to zero progress gained. Ship Rock gained the notoriety of being the last great challenge in North America, and there was even a rumored reward of $1000. The early pioneers were determined and brave. Robert Ormes and other members of the Colorado Mountain Club made several attempts, and although they pushed higher than anyone else had previously climbed, they could not make a route work. The most memorable of Ormes attempts took place in 1937 and ended above the Black Bowl in the Colorado Col. Faced with a steep basalt rib, he attempted to lead a difficult pitch straight upward toward the summit. Far above his last piece, a foothold broke sending Ormes plummeting toward a single shabby piton placed only two inches into the rock. The force of the 30-foot fall slammed his belayer into the wall and miraculously the piton held (after bending 90 degrees). Shaken, the two retreated and Ormes soon wrote an article entitled, "A Bent Piece of Iron" chronicling the incident. It was published in the Saturday Evening Post and only served to fuel many's desire to summit Ship Rock. The CMC's efforts were taken over by the Sierra Club, and in October 1939, a party of their members assembled at the base. David Brower, John Dryer, Raffi Bedayan and Bestor Robinson all traveled from California for their attempt and proved well resourced with every ounce of beta available on the route. Their gear consisted of many things, but most notably they carried 1,400 feet of rope, 70 pitons, expansion bolts, and drilling equipment.

Working their way up the Black Bowl, the Sierra Club reached the basalt rib where Ormes fell in the Colorado Col. Deciding that the climbing above was too difficult, they instead climbed over the Colorado Col and made a series of rappels down the Rappel Gully to the other side of Ship Rock. Here they found themselves faced with a difficult traverse across a seemingly blank face to reach the easier upper slopes of the Honeycomb Gully. As they carefully traversed the face, they placed two expansion bolts to compensate for the total lack of standard protection opportunities. On the other side, they found themselves in a small cave above the immense walls of the lower Honeycomb Gully. With the cave's overhanging roof blocking upward progress, it took an entire days work to pass the Double Overhang via a short aid pitch. Finally on easier ground, the Sierra Club quickly found themselves at the now famous Horn. After throwing a rope over the feature, they stepped out over the immense west wall (and 1,800 feet of exposure) to climbed directly to the ledge above. One last pitch and some exposed scrambling later they stepped triumphantly onto the summit block. The first party retraced the route back down and celebrated their success. It took a decade before another party reached the summit again.

Shawn on Der Freischutz

My path crossed with Tse' Bit'ai by complete accident in 2007. Over the previous few years my climbing skills had grown and I had begun to read mountaineering literature. I was reading Gerry Roach's first autobiography Transcendent Summits, and I found myself re-reading the chapter, "The Rock with Wings". Intrigued, I quickly searched for any information I could find on Ship Rock. Instantly hooked by the mysterious rock, I absorbed everything I could find on the route and had an strange assurance that my chance to experience Tse' Bit'ai would come. Three years later I rarely thought about Ship Rock and had been keeping myself busy by pursuing numerous classic routes in the Flatirons. Finding that my regular partner's schedule had become busier than usual, I had posted on 14ers.com looking for someone interested in the Fatiron. I received an almost immediate response from another Flatiron regular named Shawn. We soon met up to climb and I enjoyed his company and affinity for the same obscure routes that I did. Not long afterward and several climbs later, I received a call from Shawn saying that he had plans with a friend to climb Castleton but needed an extra set of cams. He said that he really wanted Castleton, but mentioned that his partner would be up for other routes if they couldn't get the additional gear. As he casually listed their other options, the name Ship Rock went by. I perked up instantly as the fire suddenly rekindled in me. I sent my gear with Shawn and began digging through the materials I had saved on Ship Rock. As soon as they were back, I emailed Shawn's friend about getting together to climb Tse' Bit'ai. His name was Noah, and he wrote back saying that he had plans with another partner to climb Ship Rock in a week. He asked his partner and told me I would be welcome to come along. My excitement skyrocketed, and I couldn't believe that it was falling into place. As we made final preparations, Noah's partner bailed and it came down to just us. We would climb over Halloween weekended. Our plan was to leave Thursday right after school, climb on Friday, and be back on Saturday. We decided to carry two 60 meter ropes, a single set of cams, several alpine draws, and lots of additional webbing. Finally ready, we were off!

Moonlight

The drive was long but fairly uneventful. We left Denver at about 5pm and cruised into the frosty mountains. Our lively conversation kept us awake through the night as we passed hundreds of miles of sparsely-populated land. We pulled off onto the dirt road outside of the town of Shiprock at 2am and slowly worked our way into the lonely desert by moonlight. Tse' Bit'ai loomed in front of us, and since our excitement could barely be contained, all we could manage was a whispered, "There it is!". As soon as we decided the car couldn't rumble any further, we pulled off and threw our sleeping bags directly onto the dusty road. Throughout the night I slept about 30 minutes total. I simply could not take my eyes off the rock as the moon slowly moved its shadow past us. Periodically in the night, I heard rocks tumbling down the massive cliffs and a few lonely coyotes howled before coming to sniff at our bags. The cold desert air felt full of energy and I enjoyed the anticipation of the dawn to come. Finally the sun cracked the horizon and as the sky turned crimson, we began to gather our gear. Stuffing our sleeping gear into the car, we shouldered our packs and were off.

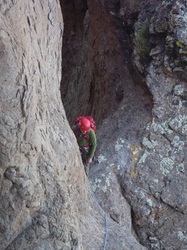

The dawn air was crisp, and my thermometer hovered at 30 degrees. Moving up toward the massive rock, we began an ascending traverse around to the west. Our eyes scanned the walls trying to view possible routes, and I noted a deep gully as we passed below. This was the Longs Col and home to another route, but more importantly to us, this would be the spot were we would rappel back to Earth if we were successful. As the trail steepened toward the Black Bowl, it did not take us long to reach the large cave that staunchly defends Ship Rock from outsiders. Stopping briefly, we looked up Spinnaker Tower and marveled at its size and unique geology. Its pale rock stood in stark contrast to the crumbling basalt that formed the Black Bowl. Tattered pieces of webbing could be seen leading up Spinnaker giving perspective to its walls. Although appearing only a hundred feet tall, it towers close to 600 feet from the base. Imagining early climbers struggling up the difficult-looking chimney splitting the face, I admired their bravery and determination. Turning back to the task at hand, we discussed how to overcome the cave. Stepping up onto the cheater stones immediatley under the overhang, I felt for a descent hold to pull over the roof. Meanwhile, Noah went to investigate the original route up the steep, narrow ledges on the right wall. On the overhang, everything felt greasy/sloping and I hopped back down with doubt. Noah soon came back saying that the ledges looked good. He also liked the idea of following the pioneer's footsteps as much as possible. Agreeing, we quickly racked up, flaked the ropes, and started up.

The dawn air was crisp, and my thermometer hovered at 30 degrees. Moving up toward the massive rock, we began an ascending traverse around to the west. Our eyes scanned the walls trying to view possible routes, and I noted a deep gully as we passed below. This was the Longs Col and home to another route, but more importantly to us, this would be the spot were we would rappel back to Earth if we were successful. As the trail steepened toward the Black Bowl, it did not take us long to reach the large cave that staunchly defends Ship Rock from outsiders. Stopping briefly, we looked up Spinnaker Tower and marveled at its size and unique geology. Its pale rock stood in stark contrast to the crumbling basalt that formed the Black Bowl. Tattered pieces of webbing could be seen leading up Spinnaker giving perspective to its walls. Although appearing only a hundred feet tall, it towers close to 600 feet from the base. Imagining early climbers struggling up the difficult-looking chimney splitting the face, I admired their bravery and determination. Turning back to the task at hand, we discussed how to overcome the cave. Stepping up onto the cheater stones immediatley under the overhang, I felt for a descent hold to pull over the roof. Meanwhile, Noah went to investigate the original route up the steep, narrow ledges on the right wall. On the overhang, everything felt greasy/sloping and I hopped back down with doubt. Noah soon came back saying that the ledges looked good. He also liked the idea of following the pioneer's footsteps as much as possible. Agreeing, we quickly racked up, flaked the ropes, and started up.

The opening pitch was rated 5.6 and proved loose and awkward. Offering positive holds, the blocks were not all trustworthy, and passage was interrupted by foliage and a short downclimb. As I seconded the pitch, I enjoyed knowing that these moves prevented any non-climber from getting off Earth and onto Ship Rock. Meeting Noah, he took me off belay, and I scrambled up to the start of the Black Bowl. It was hard to ignore the pressing silence and energy of this sacred place. The walls rose forming a strange cathedral around us, and I felt that any noise would be a disturbance to the sanctuary. As I crossed to the far side of the Black Bowl, I pulled my rope toward me and grumbled when the loose rock snagged it at every opportunity. With my rope coiled at my feet, I turned to the broken wall that rose up the left side of the Bowl. We carefully began to solo our way up the low fifth-class terrain, taking care not to knock rocks down on each other. One steep step caused us to briefly pause before carefully tiptoeing upward. As we gained elevation and neared the top of the Black Bowl, we followed the crumbling ledges back to the right before scrambling up a final dirty pitch to the top of the Sierra Col.

To quote Eric Bjornstad from his original Desert Rock guide, "The rim of the south wall of the Black Bowl is split by a deep, narrow gully, that leads to the Sierra Col, above which towers the Fin, or north summit. It is easy to climb to the rim of the Bowl to the right of the gully - the original climbers went this way. Unfortunately, in order to reach the Colorado Col on the north side of the Fin - and the rest of the route - it is necessary to cross the Sierra Col, the notorious "rubbed out portion" of the crest, a short but difficult and alarming pitch."

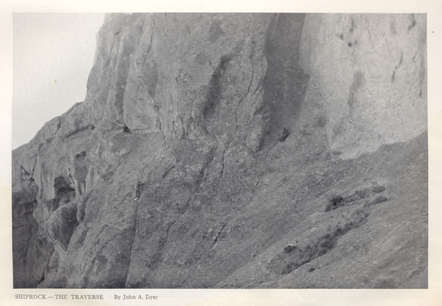

Following in the footsteps of the pioneers, we now found ourselves atop the Sierra Col looking across the "alarming" traverse to the Colorado Col. Noah stood at a belay stance on a narrow fin of rock that resembled a diving board. To his left was a sharp drop into the Sierra Col, and the right was filled with air down into Longs Col. I eased out to join him at the already overcrowded plank and passed him a bight of rope to clip to the anchor. Once secured, I put him on belay and we transferred gear. I watched Noah crack a smile as I gently lowered him down to clean the possible pendulum potential. He quietly called back "Climbing", and weighted the first hold. His handhold promptly disintegrated under his touch, and he swung back to the wall. Cursing, he stepped further left and reached up high on the basalt. Finding a descent hold, he carefully pulled upward to overcome the traverse and was smiling back from the Colorado Col. Scrambling nimbly to the top of the Colorado Col, he clipped an old bolt and put me on belay. I couldn't help but frown as I looked across the unprotected traverse. To reduce the fall potential for myself, I gingerly stepped down into the Sierra Col before beginning the traverse. Finally committing the questionable basalt blocks, I pulled up over the obstacle. As I neared Noah, I saw something that made me pause. Right in front of me I saw a strange crimson hue seemingly scratched into the rock. The mark's resemblance to blood was uncanny, and I couldn't help but imagine the great battle that had occurred here.

Following in the footsteps of the pioneers, we now found ourselves atop the Sierra Col looking across the "alarming" traverse to the Colorado Col. Noah stood at a belay stance on a narrow fin of rock that resembled a diving board. To his left was a sharp drop into the Sierra Col, and the right was filled with air down into Longs Col. I eased out to join him at the already overcrowded plank and passed him a bight of rope to clip to the anchor. Once secured, I put him on belay and we transferred gear. I watched Noah crack a smile as I gently lowered him down to clean the possible pendulum potential. He quietly called back "Climbing", and weighted the first hold. His handhold promptly disintegrated under his touch, and he swung back to the wall. Cursing, he stepped further left and reached up high on the basalt. Finding a descent hold, he carefully pulled upward to overcome the traverse and was smiling back from the Colorado Col. Scrambling nimbly to the top of the Colorado Col, he clipped an old bolt and put me on belay. I couldn't help but frown as I looked across the unprotected traverse. To reduce the fall potential for myself, I gingerly stepped down into the Sierra Col before beginning the traverse. Finally committing the questionable basalt blocks, I pulled up over the obstacle. As I neared Noah, I saw something that made me pause. Right in front of me I saw a strange crimson hue seemingly scratched into the rock. The mark's resemblance to blood was uncanny, and I couldn't help but imagine the great battle that had occurred here.

Looking off the other side and into the sun, we couldn't wait to be in its warmth. Congratulating each other to finally be at the top of the Black Bowl, we passed by the site of Orme's brave attempts and carefully worked our way down the slabs into the rappel gully. The top anchor consisted of several rusted bolts with a tattered array of faded webbing, making it less than inspiring. Reaching into my pack to find the extra webbing, I came up empty handed. In our early morning excitement, we had forgotten to grab that final bag from the already overstuffed trunk. With a few cordelettes between us, we figured we had enough to replace anything that was in truly horrible shape. Not wanting to waste our now precious cord, we decided to trust the anchor. Clipping in one sling for a backup, Noah would rappel first as I watched closely. If I felt it would hold, I would un-clip our backup and rappel on the tattered gear alone. As Noah gingerly weighted the rope I could hear the slings groan audibly under the new stress. Fortunately, the slings seemed to take the new weight in stride and held strong as Noah slid down the rope. To reach the next anchor, he had to step over several large blocks wedged in the gully. As he stepped onto one seemingly innocent microwave-sized block, it became loose under his feet and disappeared down the slot. The following sound was both horrifying and amazing. As the rock flew toward Earth, we could only listen as its crashing bounces alternated with seconds filled with charged silence as it fell through empty air. During its sixty-second decent, there were moments of silence that had us holding our breath. This was a stark reminder of the massive cliffs we were above. As silence returned to our temple, we resumed our work. Noah clipped to the anchor, and as I joined him, he told me "You're going to love this!". Craning my neck, I saw the next "anchor" was a single old bolt with a mallion attached. Great! At least there was no ancient webbing to trust. We did the next rappel carefully, and as we gathered on the small ledge, we looked back up rappel gully. Beginning to pull the ropes down, we felt into total silence. Without the ropes ensuring a return up rappel gully, we would have no choice but to reach the summit and find the supposed rappel anchors that had been placed in 2005. Fully committed and now on the famous breccia tuff that forms upper Ship Rock, we prepared for the traverse to the Honeycomb Gully and the rest of the climb.

Looking across to the famous traverse to reach the Honeycomb Gully, we spied several pieces of ancient fixed gear. Although rated 5.8, this was said to be well protected and fun. "I have to lead this." Noah quickly volunteered. As he started across with a grin, it was obvious that the sun had warmed our enthusiasm. Disappearing around the corner, I silently fed out rope as the minutes stretched on. As I was beginning to wonder if everything was alright, I heard a faint "off belay". Anxious to step out into the sun, I moved smoothly past the first pin. Enjoying such easy terrain I un-clipped the second piece and stepped into the light. As my eyes adjusted, the view made me freeze. With Noah out of sight around a corner, the rock reared steeper to block the path. The rope sagged 150 feet across the face in a mocking facade of safety and there was not a single piece of gear as far as I could see. "Where did you go?" I called out. "I have no idea...don't fall." echoed back. Feeling a knot start to grow in my stomach I slowly started tiptoeing across the impossible looking slab. I reminded myself of the similar traverses I had done in the Flatirons across other improbable faces, but could not shake the reality that this situation was much more serious. My sense of security grew faintly with each step I took and I could sense safety nearing. With Noah just about to come into view, I felt myself jerk downwards. The large flake that I balanced on exploded under my feet, and I began to slide down the face. My mind reeled as I quickly played through the enormous pendulum fall I was about to endure. My reflexes took over and my arms snapped outward. Cursing loudly, I grabbed for whatever was available and to my surprise stopped almost immediatley. As it sunk in that I was no longer falling, I took in my situation. I had slid only a few feet but was now perched precariously below the path of least resistance on extremely friable rock. Not about to waste time, I saw a small protrusion in the rock that would serve as a directional on the rope if I could get under it. I scooted down and across the wall as a shower of crumbling rock tumbled into the lower Honeycomb Gully. Reaching the bulge, I battled my way back up towards the route and popped up directly below Noah's belay.

"Keep it down man! Did you fall?" he asked.

"Not much I could do, a little too close for comfort. So much for well protected." I replied.

"That's why it took me so long. I definitely didn't envy you after I made it over here."

Not wanting to linger, we quickly shifted gears to moving back up. For the first time we started to feel worn from the hurdles we'd been jumping all day. Noah led up a short 5.9 crack and continued up and over the Double Overhang in a single pitch. Although short, the crack proved to be very awkward and the dreaded Double Overhang went smoothly. I could feel the air tug at my heels as I stepped over the void above the lower Honeycomb Gully and moved carefully up to the belay. Happy to have to have the summit in sight and faced with some easier scrambling, we flaked the ropes and prepared to solo up the Honeycomb Gully.

"Keep it down man! Did you fall?" he asked.

"Not much I could do, a little too close for comfort. So much for well protected." I replied.

"That's why it took me so long. I definitely didn't envy you after I made it over here."

Not wanting to linger, we quickly shifted gears to moving back up. For the first time we started to feel worn from the hurdles we'd been jumping all day. Noah led up a short 5.9 crack and continued up and over the Double Overhang in a single pitch. Although short, the crack proved to be very awkward and the dreaded Double Overhang went smoothly. I could feel the air tug at my heels as I stepped over the void above the lower Honeycomb Gully and moved carefully up to the belay. Happy to have to have the summit in sight and faced with some easier scrambling, we flaked the ropes and prepared to solo up the Honeycomb Gully.

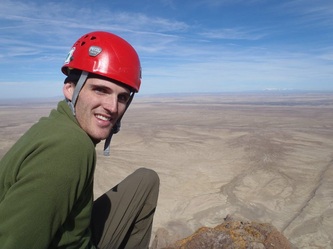

Stepping into the Honeycomb Gully was a wonderful feeling and we moved smoothly up toward Cliff Monsters nest. This was near the site of the mythical battle and our spirits moved up with us. For the first time, we could see the summit and the famous Horn towering above us. As I glanced back to snap a few photos, I was given a stark reminder. Although we were on easier terrain, a slip would send us directly to God. Honeycomb Gully arcs up smoothly and is reminiscent of moderate east face routes in the Flatirons. A thin trickle of ice ran down the center and we moved carefully around it. Other than one steep, thought provoking step, we moved smoothly upward and soon stood at the top of the gully in Cliff Monster's nest. We belayed up a short chimney and were immediatley below the famous Horn Pitch. Tilting our heads back up the impressive feature, Noah simply said, "Your lead!" Starting to feel exhausted, I meekly mumbled, "I'll give it my best. I think you just want a photo of you coming up from above." Noah simply smirked as we traded gear and I visualized the opening moves. My mind was not feeling centered for the lead and I struggled with the idea. Pulling myself together, I started up. The initial crack was slightly overhanging and the rusted pitons were less than inspiring. I clipped the old pieces as I struggled upward. As I did the famous step out onto the face, I stopped. Stepping out into the sun, my mind cleared instantly. I imagined the pioneers standing exactly where I stood feeling the historic summit within their grasp. Admiring were I was, I traced the path I would follow up then turned my eyes slowly downward. I was poised above 1,800 of sheer rock and empty air stood between me and the desert floor. The car was a tiny speck directly below my feet and I smiled as I took it all in. Back to the task at hand and with a clear head, I moved easily up the questionable flakes to the top of the horn. After clipping the single bolt and extending the belay, I brought Noah up while snapping photos of him smiling all the way. With one last technical pitch between us and scrambling terrain to the summit we felt elated. Noah made a quick lead of the final 5.8 crack and as I joined him we un-roped and moved up. As we closed in on the summit, the world seemed to expand around us. The rock shrank and the air increased until we finally moved onto the summit plateau. Pausing only to verify the rappel anchors, we both untied and moved onto the summit block together.

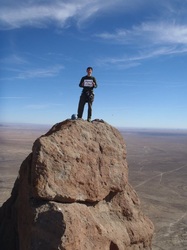

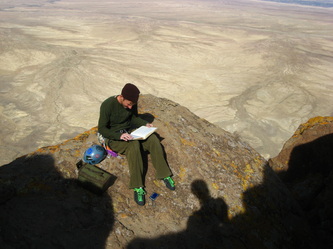

The top of the north summit is where Tse' Bit'ai's up-stretched wings finally relent to Sky. The final touch of rock jutting upward into nothingness is the most astonishing point in the area. The mythical block rises above a small plateau and teeters above thousands of feet of air. The barren landscape allows the view to stretch on for hundreds of miles in every direction. As we tiptoed onto the tiny exposed block we congratulated each other then fell into silence. The view was stunning and the reward was a sweet end to all the hard work. Surrounded by nothing but vast quantities of air, I thought of the mystical Navajo climbers perched atop Tse' Bit'ai. I let the rock's energy flow through me as I enjoyed our perch and understood its significance.

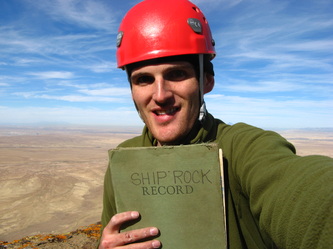

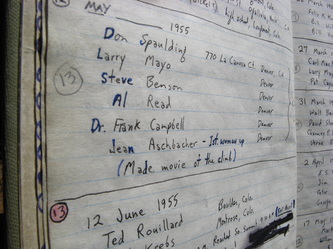

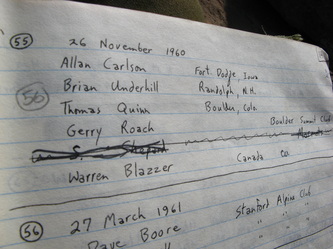

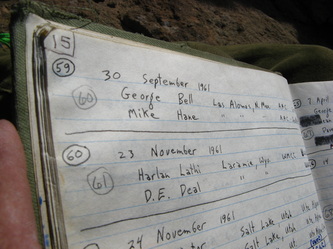

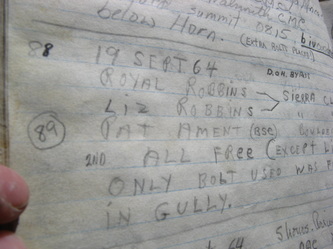

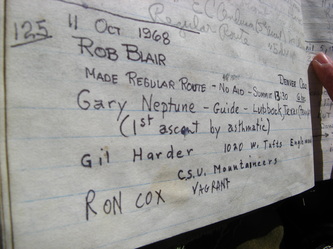

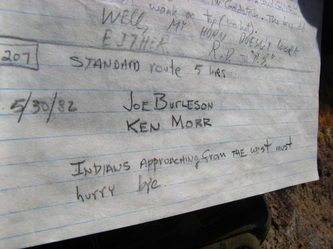

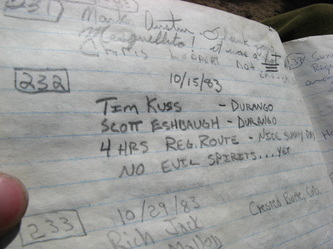

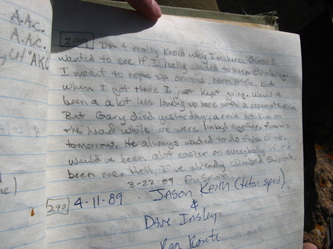

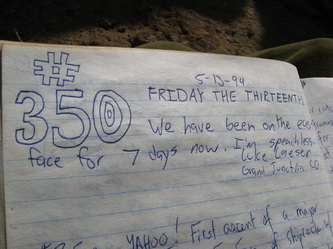

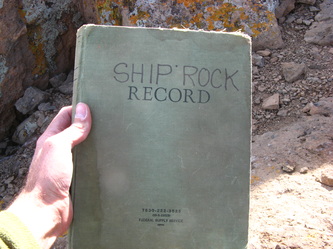

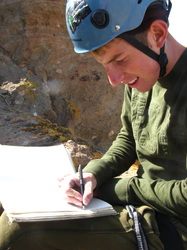

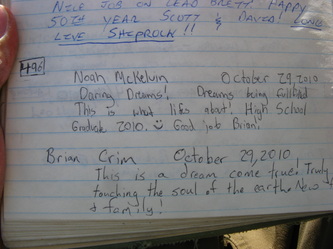

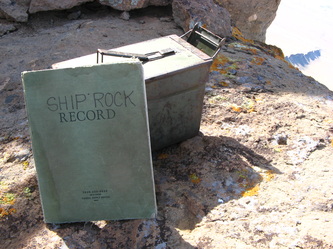

After sitting on top for long enough to emblazon the summit into our

memories forever, we sought the fabled summit register. The book goes

back to the original ascent and has every party to summit written in.

Many famous climbers have visited this sacred place and have inscribed their names. We took time to read every page and take numerous photos. Signing our names felt amazing and I imagined becoming part of the history. We were the 496th party to reach this elusive summit. After spending close to an hour on top, we decided it was time to head down before finding ourselves caught in the early October twilight.

Taking one last look around, we carefully stowed the summit register and wormed our way under a large block to reach the rappel anchors. The late afternoon air had grown chilly and the rappels felt more ominous in the shade. The only information we had was that there were four rappel anchors. They were all meant for double-rope rappels down a sheer face to reach the top of Longs Col. We were aiming for anchors we'd never seen, and if anything went wrong we could be stranded hundreds of feet above the ground. Threading the ropes through the anchors, Noah clipped in and I watched him disappear down the face. The wind was picking up and as the moments passed, I started to wonder if something was wrong. Finally I heard a distant "off belay" and clipped in and slid down. As soon as I saw Noah he told me what had happened. There was a large horn of rock that could be passed on the left or right. He had chosen climber's left, and as soon as he passed the feature, he saw the anchors were on the right and now out of reach. He had thankfully managed to pendulum his way and grab the anchor. I paused to flip the rope over the other side of the feature and was soon at the anchor. In contrast to the first shiny anchor, this was a tattered mess of ancient webbing and rusty bolts. Thankfully, the mess seemed equalized and thick enough to hold. Pulling the ropes down, we fed them through the anchor and were off. As I followed Noah down to the third station, I discovered a dangerous problem. The wall was covered in a thin layer of crusty rock that crumbled to the touch. This caused a constant shower of rock-fall onto the next anchor as I rappelled. Carefully as I could, I came down, but did send the occasional rock onto Noah. Thankfully, nothing major broke loose and I apologized when reached the anchor. The rope reluctantly pulled down and we threaded the final anchor. Noah made quick progress down to the top of Longs Col and cheered a happy "Off Rappel!!" I was tired and the ground called like a siren. Clipping the ropes through my ATC, I stepped up to un-clip my backup. Glancing down, my heart stopped. With my right hand holding my backup carabiner open, I watched my ATC pop off my harness. I had been a fraction of a second from a 200 foot fall and death because I had improperly clipped into my ATC. I thanked God that I had not un-clipped sooner, and took a moment to catch my breath and re-center myself. I carefully clipped my ATC back to my harness and re-checked it several times. I finally managed to un-clip the backup, and slid quickly down the rope. This sent another shower of debris to the Col and I was glad Noah was out of the way. I had never been happier to touch ground, and we pulled the rope while taking in the surroundings. Scrambling down to the next rappel, we passed several small caves below the towering walls. The next double-rappel went down a steep slab. The next anchor was a single bolt with a mess of webbing that had been placed on a lone boulder that sat precariously on the floor of the Col. I again joined Noah and again pulled the ropes. Ducking as more rocks came tumbling down on us, we watched the rope fly free. Further down, the next station was a strange assortment of rusting star-bolts and missing hangers. We threaded the weird anchor and motored further down the Col. We un-clipped and had the unfortunate surprise that the rope would not pull. The final bend in the Col had the ropes trapped and as we fought to pull them down, we realized it was a lost cause. Swearing, Noah hastily clipped in and quickly jugged up the rope and out of sight. I enjoyed the location we had earned as I leaned against the wall to dodge the rock-missiles that battered down from above. The walls again felt like cathedrals and the air was still as a mausoleum. The fractured rock held a sacred energy and I soaked it up. Finally Noah returned and the ropes pulled. A short scramble put us at the final rappel station. Noah happily threaded the anchor and was soon on the ground. He whooped a celebratory "Off Rappel!!" and I smiled. I new that I would also soon feel the joy of being back on Earth. I clipped in to rappel and took one last glance around. I doubted that I would ever return, but made sure my memory had enough to never forget this place. Sliding smoothly down the rope I stepped softly onto the ground. I hastily pulled the ropes and sat down for the first time since the summit. My feet were numb and happily flexed as I peeled off my rock shoes. We had been off the ground for ten hours and were elated at our accomplishment.

As we sat at the base of Tse' Bit'ai, my stomach growled audibly. As wonderful as the climb had been, it was time to return to the world. We shouldered the gear and moved steadly toward the car. Noah's car looked lonely sitting out in the desert, and we set our gear down to snap several photos of Tse' Bit'ai and our surroundings. The boulders that littered the base had appeared like specks from above. From the desert floor we discovered they were actually the size of small houses. The Great Dike loomed and drew a bold line across the landscape. As we took a final photo together, we suddenly heard voices. Exchanging a surprised glance, we loaded our gear just in time to see a white van driving tourists to the base. They were giving a guided tour and as we passed, the passengers all waved and smiled. We slowly began to maneuver out the rutted dirt road towards the main thoroughfare. Stopping one last time, we scrambled up onto the Great Dike. Luck had it we arrived just in time to see Sun touch Earth. We sat in silence and soaked in the last kiss of light on Tse' Bit'ai. The great Bird held the sun's rays longer than anything else around and seemed to glow. As we drove off, we watched Tse' Bit'ai until it slowly dissapeared from view. I imagined the Great Bird's gift to the People and its ultimate sacrifice. Tse' Bit'ai stood proudly above the desert floor as the sky burned behind it. This was a fitting end to our day and will be forever etched into my memory.

"We love not only the taste of freedom but even more the smell of danger. We take pleasure in the consumation of mental, spiritual, and physical effort in the achievement of the mountain's summit which brings the three together."

- Ed Abbey

- Ed Abbey